"Todo lo percibo simultáneamente. Todo lo percibo a la vez y desde todos los

ángulos posibles. Formo parte de los miles de millones de vidas que me han

precedido. Existo en todos los seres humanos y todos los seres humanos existen

en mí. En un instante veo a la vez toda la historia del hombre, el pasado y el

presente." Frank Belknap Long: Los perros de Tindalos

El devenir

Hegel concibe la realidad como cambio constante, ésta se manifiesta como tiempo.

Pero el tiempo no es un mecanismo que se active automáticamente. Son nuestras

acciones las que dan lugar a su despliegue. Así, nuestra actividad biológica nos

hace surgir a la vida, el autodinamismo de ésta nos hace pasar a través de un

proceso que nos convierte en una célula, un embrión hasta que salimos a la luz

como bebés. Este autodinamismo continúa fuera del vientre de la madre y pasamos

a la condición de niños, jóvenes, adultos ancianos y acaba inevitablemente en

nuestra muerte. Durante ese mismo periodo realizamos acciones que nos hacen

pasar de una condición social de un tipo de persona a otra, de solteros a

casados o divorciados, estudiantes, empleados, desertores etc. A un nivel de

mayor complejidad la sociedad sigue la misma ruta: de pequeños grupos pasamos a

convertirnos en tribus, aldeas, pueblos, Estados nacionales, imperios, tiranías,

democracias, etc. Y así, continuamente, pasamos de ser algo a ser lo contario de

lo que éramos anteriormente. El concepto de devenir refleja esta condición de

nuestra temporalidad: pasar de la condición de ser algo, mientras transitamos a

ser otro, para finalmente no ser más algo. Nuestra acciones, voluntarias o

autónomas e inconscientes, construyen una identidad transitoria que nos conduce

a otra condición, mientras niega la anterior, para finalmente dejar de ser. Esta

perspectiva parece ser pesimista con respecto a nuestro destino individual y lo

es si sólo lo vemos desde ese momento de la temporalidad. En realidad, nuestro

ser individual, parcial y efímero, es parte de uno más amplio, permanente y a la

vez dinámico que incluye todos los momentos y entes individuales, así como el

legado que han dejado, por lo cual Hegel no dudo en llamarlo Absoluto.

Apolo y Dafne: Bernini

Del Espíritu Subjetivo al Espíritu Absoluto

En este tránsito del ser particular al ser absoluto emerge un fenómeno llamado la conciencia, que también se despliega en ese espacio de la transformación humana que llamamos Historia. El tema de la conciencia que conoce un mundo, o de un sujeto frente a un objeto, es esencial para toda la filosofía, temática que al tratar de especificar el tipo de relación que tienen ambos polos, ha sido generalmente comprendido en términos de separación y pasividad: el sujeto se deja determinar por el objeto para el empirismo, y así surge la mente humana, que permanece yuxtapuesta al objeto; en el racionalismo el sujeto, desde la mera contemplación y la pura actividad de sus mente determina el ser del mundo, en una permanente relación mental a distancia. Además, concibe esta relación como intemporal; prescinde de nuestra corporeidad, de nuestra historia, de las herramientas de la cultura que empujan el nacimiento y crecimiento del espíritu humano. Otro rasgo importante es que, tácitamente, este espíritu se concibe como el de un individuo, mientras que para Hegel ese sujeto es colectivo.

El filosofo en meditación, Rembrandt

Desde que emergemos de la naturaleza nos enfrentamos a ésta transformándola para satisfacer nuestras necesidades, el sujeto se enfrenta al objeto para transformarlo, no para contemplarlo, lo hace negándolo como naturaleza para afirmarlo como lo humanizado. No se enfrenta un individuo a la naturaleza, sino la especie, y tampoco lo hace en un momento o en una intemporalidad metafísica, sino en el tiempo del sujeto colectivo: la Historia, como ya lo habíamos mencionado. Su relación practica con el mundo transforma al objeto pero también a sí mismo como sujeto, lo cual se ve reflejado en las instituciones que funda a lo largo de la historia, en sus creaciones culturales, que nunca son homogéneas, sino heterogéneas y en sus códigos éticos y políticos., Este sujeto colectivo se transforma cualitativamente, pues sus forma de pensar lo que es la justicia, el derecho, el arte, etc. apuntan a un pensamiento dinámico que no tiene una forma fija para definir sus creaciones: así, en la política y el derecho, inicialmente la humanidad organiza sus códigos para que sólo un hombre sea libre y los demás esclavos; siglos después, este mismo espíritu humano colectivo, transformado por sus propias acciones en la historia, crea códigos legales para que todos sean libres e iguales. La mente del individuo (con sus peculiares formas de conocer: sensibilidad, y entendimiento), sólo es un momento del espíritu. En su fenomenología, la humanidad entera, que colectivamente transforma el mundo en la historia, es el espíritu pleno y completo, es decir, el Espíritu Absoluto.

Vincent van Gogh: campesina cortando paja

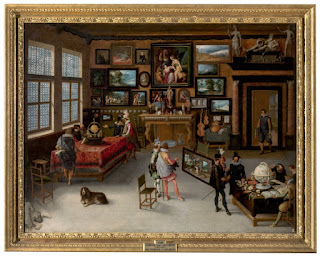

Adriaen Van Stalben: Las Ciencias y las Artes

Aunque el espíritu humano en su forma absoluta es unitario, no es homogéneo, pues la contradicción es siempre latente. Las relaciones entre los seres humanos adquieren una forma prototípica: el enfrentamiento entre amos y esclavos. En la reproducción de su vida el sujeto impregna de espiritualidad humana a la naturaleza, pero no halla eco de su grandeza en la naturaleza muda; el ser humano pleno es el que es reconocido como tal,

peor solo puede pleno en la mirada de otro. Ser reconocido como ser supremo, ante los otros hombres, parece ser una constante en la historia de la humanidad, desde “los grandes conquistadores”, hasta los hombres más ordinarios que lideran a grupos criminales, todos han tenido esta terrible obsesión. En general todos ellos se apoderan de otros seres humanos y de sujetos los convierten en objetos, animales de trabajo que satisfacen sus necesidades. Pero el esclavo es ese sujeto que se enfrenta al objeto, transformándolo y, a la vez, transformándose a sí mismo espiritualmente. Las grandes creaciones del espíritu humano son obra de los esclavos, no de los amos, aunque los nombres de los esclavos se pierden en la obscuridad del devenir.

Lógica y Dialéctica

Tradicionalmente la filosofía ha buscado atrapar la realidad mediante el uso de una lógica que define y fija las cualidades permanentes de ésta. Así podemos distinguir entre cualidades contingentes (las que tienen las cosas, pero que pueden dejar de tener sin que deje de ser lo que son) y necesarias, (las que tienen y no puede dejar de tener), de la realidad. Las sillas, por ejemplo, tienen características tanto contingentes (su color, el material del que están elaboradas, si tiene cuatro patas u otra estructura, etc.) como necesarias (un asiento individual, un respaldo, y una estructura que la dispone sin riegos de hacer caer a su usuario al suelo). Su identidad se fija sacándola del contexto en que existen las sillas para asentarla, en el pensamiento, como una estructura universal que dibuja claramente la esencia, y por ende su identidad de silla. Pero las sillas son antes materia prima, (madera, minerales, petróleo, etc.), las necesidades humanas (descansar, colocarse sentado para hacer mejor ciertas actividades), y la capacidades intelectuales y corporales para hacer sillas. Dicho de otra manera: las sillas también se ubican en el devenir, se producen, se estrenan, se usan durante determinado tiempo, se hacen viejas (se apolillan, se rompen, se hacen feas, pasan de moda, se desechan o se reciclan). La lógica ha logrado crear la imagen de la silla a partir de sacarla del tiempo y del contexto del ciclo de vida de la silla, esa imagen es como una fotografía de los tiempos en que se inventó este aparato, cuando se tenía que posar completamente quieto para poder salir bien retratado.

La filosofía anterior a Hegel, desde Parménides a Kant, pasando por el empirismo, en su esfuerzo por atrapar lo permanente de la realidad, intenta detener el fluir del devenir, interrumpiendo la acción del mundo que produce ese devenir, operando así: eliminar lo que la silla no es, que llamaremos propiedades “B”: materia prima, sus cualidades contingentes como color, material, forma; las necesidad humanas que hacen surgir la silla (que incluye también caprichos que producen sillas con materiales y formas exóticas, así como las posibilidades económica para tener sillas baratas o de lujo; la historia de los muebles, ese espacio que posibilita ampliar la gama de materiales y diseños; y finalmente su tiempo de descarte). Las sillas se definen entonces por su propiedades permanentes y necesarias (un asiento individual, un respaldo, y una estructura que la dispone sin riegos de hacer caer a su usuario al suelo). A estas propiedades las llamaremos “A”.

De esta manera tenemos, en la filosofía anterior a Hegel, que la identidad de la silla, o de cualquier ente del mundo se opera de la siguiente manera: "A = A", lo absurdo es que la silla o cualquier ente sea así: "A = B". Para tener clara la aportación original de

Hegel es importante tener en cuenta que "B" representa el mundo del devenir de las sillas que describimos en el párrafo anterior.

Es cierto que A = A o que la silla es igual a sus propiedades necesarias, pero esa es una verdad incompleta, la verdad plena y absoluta de la silla es A = B; la silla es también la historia de su devenir. La filosofía anterior a Hegel opera con una lógica de negación, de separación, de hacer esconder, para finalmente extraviar el devenir en su forma de pensar la realidad. La dialéctica hegeliana es un esfuerzo por integrar lo que ha sido negado, para poder pensar de una manera completa todo el proceso de la realidad. En la filosofía anterior un momento del devenir ha sido fijado, dando lugar a la lógica de la identidad, A = A; esto es resultado de la manera en que la filosofía intenta atrapar la realidad: desde la contemplación. Contemplar es detener la acción, dejar de hacer para que ese momento del devenir perdure. En Hegel acción y contemplación son parte de una misma realidad, igual que lo necesario y lo contingente, devenir y permanencia, los cuales están conectados de una manera no evidente; la sociedad tiene que movilizarse a lo largo de la historia, crear la realidad mediante el conjunto de su praxis, para que el filósofo pueda, después, interpretarla: «El búho de Minerva sólo emprende el vuelo a la caída de la noche.». (Hegel, 1985).

Así pasamos de pensar la

silla, con la lógica tradicional, como una esencia fija a comprenderla como un

proceso historico complejo. De la misma

manera, bajo esa lógica esencialista nos pensamos a nosotros mismos desligados de

los procesos de transformación colectiva, con sus implicaciones políticas y

éticas: al vernos como una esencia fija, nos concebimos como individuos sin

ligamento con los otros, y esto involucra competir y luchar contra ellos, en

vez de ubicarnos dentro de un proceso en el cual podemos colaborar, para

trascender nuestra natural vulnerabilidad y preparar un mejor lugar para los

que vendrán. El pensamiento no es un accesorio ornamental para nuestro estatus

social que justifique nuestro aislamiento y privilegios, sino una de las formas

de reparar nuestra omisión y comprender nuestro compromiso frentes a nuestros

ancestros y nuestros sucesores.

La silla de Gauguin, Van Gogh ¿Es esta silla solo su forma (A=A), o es también la luz que la envejece, el cansancio de quien se sentó en ella, y la historia del arte que la hizo posible (A=B)?

Hegel, el Sísifo de la esperanza

Cronos, el original padre de los dioses griegos, devora a sus hijos, así el devenir, nuestro padre, acaba por devorarnos a todos. Sísifo el héroe trágico lleva la enorme roca a la cúspide de la montaña para verla derrumbarse y está condenado a repetir este ciclo por toda la eternidad. En Hegel, como ya habíamos mencionado antes, el espíritu individual solo es un momento del espíritu absoluto. Cada persona que llega al mundo humano se esfuerza por elevar su vida a determinada cima, de pronto, las fauces de Cronos se abren, cae, y se pierde en el abismo del olvido. No obstante, esta persona, durante el breve lapso de su vida, contribuyo, de mil maneras, sin saberlo, al mantenimiento del Espíritu Absoluto. Por ejemplo, salió alegremente del hogar de sus padres, sin lograr entender plenamente la melancolía de ellos, para fundar “su propia vida”. Tuvo hijos, y cada día se esforzó, sin saberlo, para disolver a su propia familia: a lo largo de los años trabajo duramente para que sus hijos salieran, un día, fuera del hogar con la fuerza y sabiduría cotidiana para fundar otra familia. Haber hecho esto le costó muchos sacrificios que acabaron por minar su vida, no le importo, al contrario, esta renuncia lo hacia una persona feliz, esta felicidad no es un anhelo individual, sino el acto de dar vida a la vida y ayudarla a hacerla crecer. Las revoluciones sociales no son algo muy distinto, alguien lucha y muere para darle libertad a otra generación. Estas acciones son uno de los más finos hilos de la realidad del Espíritu Absoluto, sin éstas, no podría existir.

Francisco de Goya: Cronos devorando a su hijo

El misticismo hegeliano y Dios

Dios está en todos lados, todo lo sabe y lo ve todo, mientras que el individuo está en un momento y un espacio finito, su mirada es de poco alcance y su conocimiento del mundo es fragmentado. Hegel usa una bella metáfora de origen místico para expresar todo el esplendor del pensamiento humano colectivo, de esa humanidad que está en todos lados,

que lo sabe todo y lo ve todo, (pues todo lo que puede conocer es producto de su praxis), de ese espíritu de pretensiones omniabarcadoras presente en sus creaciones más excelsas: mito, arte, ciencia, tecnología y filosofía, ese espíritu que no solo es actividad, sino memoria colectiva, y de trabajo, pues el conocimiento generado en el pasado guía la exploración hacia el futuro. Es el Espíritu revolucionario que al final del vuelo del búho de Minerva, esperaba que toda la humanidad fuera libre, más creativa, más digna, asemejándose a Dios.

Desde lo cotidiano de tu mirada llegar a lo aboluto

Parafraseando a Frank Belknap Long, el sujeto colectivo que describe Hegel no es sino los millones de vidas que nos han precedido, cada una de estas vidas es un momento del Espíritu Absoluto. Somos una totalidad conectada a través de la historia y la cultura, pese a nuestro anonimato y nuestra amnesia sobre la existencia concreta de esas personas. El Espíritu Absoluto existe a través de todos los seres humanos y todos los seres humanos existen en él.

Por nosotros el Espíritu Absoluto lo percibe todo y desde todos los ángulos posibles. Esta reflexión es un intento dialectico que busca a través de lo efímero del que escribe y del que lee, colocarse en esos ángulos, en la visión de todos y cada uno de nosotros, para, en la fugacidad del instante, comprender nuestra pertenencia con toda la historia de la humanidad, su pasado, su presente y nuestro papel vital en la construcción del futuro. Tú, lector, con tu complicidad eres el Espíritu Absoluto: lo personal y lo universal fundidos.

Miguel Ángel Buonarroti: Creación de Adán (detalle)

Epilogo: Esta invitación a

pensarnos como parte de un todo histórico es, en el fondo, una propuesta

política y vital para nuestro tiempo presente. Por ello, me parece crucial

aclarar la intención que guio esta relectura de Hegel: Este trabajo fue realizado buscando cumplir dos objetivos: 1) presentar a Hegel para cierto tipo de lectores ajenos al ámbito de formación académica filosófica, pero que al mismo tiempo tengan un genuino interés y que encuentren placentero el acercarse a este tipo de pensamiento. 2) Es inevitable hacer una interpretación y una relaboración conceptual cuando se presenta el trabajo de otra persona, especialmente si es un autor genuinamente filosófico y tan distante en el tiempo y espacio del nuestro; por lo que, me siento obligado a aclarar desde qué idea escribo esta

interpretación: Hegel es un autor muy importante para pensar nuestro tiempo, en que predomina una forma de pensar a las personas como “individuos” que viven yuxtapuestos en algo fragmentado llamado “sociedad”, viviendo su experiencia del mundo en el aquí y en el ahora. Hegel por el contrario nos invita a repensarnos como parte de algo más amplio que los límites de nuestra subjetividad, y nos hace ver que formamos parte de una realidad que rebasa nuestro tiempo subjetivo y nos invita a compartir un sentido de vida que nos liga a las generaciones del pasado y del futuro, buscando hacer de este mundo un lugar más digno para todos.

Referencias bibliográficas:

GARAUDY, R. (1974). El pensamiento de Hegel, Seix Barral, Barcelona

HEGEL, G. F. (2000) Enciclopedia de las ciencias filosóficas Juan Pablos, México

----------------- (1985) Fenomenología del espíritu, Fondo de Cultura Económica, España.

---------------- (1985) Filosofía del Derecho, U.N.A.M. Colección Nuestros Clásicos.